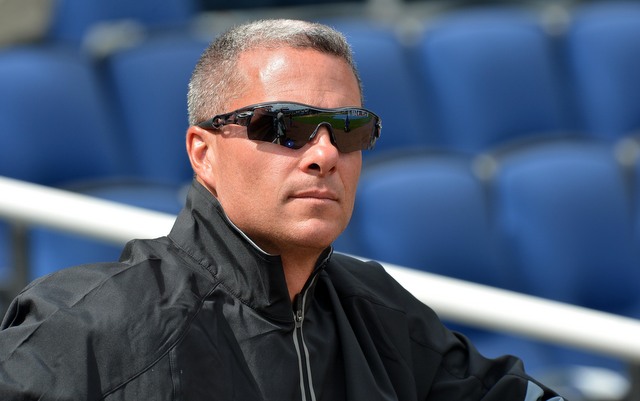

The Royals have saved Dayton Moore’s job this year. Or maybe

it’s Dayton Moore that saved the Royals this year? Depending on whom you ask,

Dayton Moore should or shouldn’t be fired. And while the thought process is a

difficult one, there is probably no one clear answer at this time. And while I

would love for you to make up your own mind with your own opinions on the

future of Dayton Moore, let me put some thoughts out there from a managerial

standpoint.

When managing a company, there are many things that managers

have to consider: operating leverage, return on investment, net operating

income, sunk costs, etc. And while I’m not nearly educated enough to write a

book about it, I am just educated enough to put some bullet points up here on the

similarities between managing a company and being general manager of a baseball

team. Intertwined in my descriptions will be my thoughts on Dayton Moore.

·

- Let’s start with a growth-share matrix. A growth-share matrix is a portfolio-planning method that evaluates a company’s strategic business units (SBU’s) in terms of market growth rate and relative market share. This definition is usually followed with a chart you might have seen in a high school or college business class.

- While any analogy will have holes in it, stick with me on this one while I switch some terminology around to compare it to baseball. Using this matrix, I think it’s fair to say that Dayton Moore traded a star for a cash cow – that, of course, meaning Wil Myers for James Shields.

- Cash cows are log-growth, high-share businesses or products, and thus they produce a lot of the cash that the company uses to pay its bills and support other SBU’s that need investment. This is what James Shields has brought to the Royals. He stabilized the rotation, eats innings, and helped make the pitching staff as good as it is. He made the whole team better.

- Unfortunately, cash cows don’t stay cash cows forever, and as good as James Shields has been this year, he only has one more year of team control left following this season. It’s examples like this that make finding stars which can eventually turn into cash cows so important for businesses and baseball teams alike. The Royals had that star, and his name was Wil.

- To play devil’s advocate, however, what if we shouldn’t consider Myers a star at the time he was traded? After all, he had yet to take a swing at the major league level. That would make him a question mark, according to the matrix. Question marks require a lot of cash to hold their share, but can turn into stars if the right course of actions are taken. Well, Myers had been and dominated the minor league levels for some time, and was about as close to a star before entering the Majors as one could be, but let’s forget that right now. A critical part of a manager’s job is to correctly identify stars from the question marks. If Dayton Moore didn’t think of Myers as a potential star, and that’s why he felt good about the Shields trade, then he made a critical error in his judgment. If Moore thought Myers would be a potential star, but still thought a cash cow in the present was the best course of action, then I believe he still made a critical error in judgment.

- Enough with the weird names and references to matrices, let’s go to operating leverage! This is a measure of how sensitive net operating income (NOI) is to a given percentage change in dollar sales. This is going to be a big stretch, but just go with me on this one.

- Increased variable or fixed expenses affect the amount of operating leverage that a company has. Higher variable costs with lower fixed costs make for a lower operating leverage. Lower variable costs with higher fixed costs make for higher operating leverage. To summarize, companies with higher operating leverage have a higher ceiling but a lower floor than companies with low operating leverage.

- When it comes to baseball, a young player with many years of inexpensive baseball ahead of him is about as close to a fixed expense as you can get. A guy with only a couple of years of team control, at a high variance position such as pitcher, would be what I consider a variable expense. Teams like the Royals can’t afford to trade fixed expenses for variable expenses. They need a high operating leverage, because in such an unfair game as baseball is on the salary cap side, the higher the leverage, the better the chance that when the Royals are ready, they are REALLY good.

- While James Shields made the team better this season, the ceiling is no longer as high as it would have been with Wil Myers.

I hope what I stated above makes

sense. There are some flaws to using the above to judge Dayton Moore; first

off, I’m really only looking at the decision to trade Myers. I don’t talk about

other moves he’s made, such as Guthrie for Sanchez or Santana for someone I’m

not even taking the time to look up, but these are important to the evaluation

process. The Myers trade, however, sticks out more than anything else, and is

what I would consider almost unforgivable. But going forward, as any good

manager would tell you, the Myers trade is a sunk cost, and should be considered

irrelevant when deciding on Moore’s future. And when looking at it this way,

and hoping the Royals are now ready to really go for it next year, I think

Moore has earned another year in Kansas City.

But this year will be remembered

for one of two reasons for Royals fans going forward: 2013 was either the year

the Royals turned the corner or the year the Royals traded a cornerstone.

All definitions I used are credited to:

Garrison, Ray H; Noreen, Eric W; Brewer, Peter C. Managerial Accounting. McGraw-Hill Irwin. New York. 2012.

Kotler, Philip; Armstrong, Gary. Principles of Marketing. Pearson. New York. 2013.

Bateman, Thomas S; Snell, Scott A. Management: Leading & Collaborating in a Competitive World. McGraw-Hill Irwin. New York. 2013.